- by New Deal democrat

Prof. Brad DeLong reposts an essay on inequality of opportunity from Angus Deaton:

Even if we believe that equality of opportunity is what we want, and don't care about inequality of outcomes, the two tend to go together, which suggests that inequality itself is a barrier to equal opportunity.What about envy of the rich? Economists have a strong attachment to something called the Pareto principle ...: If some people are made better off and no one is made worse off, the world is a better place. Envy should not be counted....

....

I beg to differ. The Pareto principle is an extremely conservative restriction that entrenches existing inequalities of power and wealth in place, virtually in perpetuity.To worry about these consequences of extreme inequality has nothing to do with being envious of the rich and everything to do with the fear that rapidly growing top incomes are a threat to the wellbeing of everyone else.There is nothing wrong with the Pareto principle, and we should not be concerned over other' good fortune if it brings no harm to us....

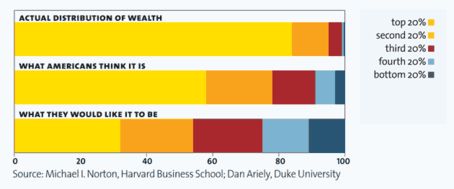

Let me explain. Below is a graph taken from a recent Harvard and Duke study, in which they asked Americans what they thought the existing distribution of wealth is, and what they think it should be, comparing those with the actual distribution of wealth:

Americans think the top 20% owns about 55% of the wealth. They think a fair distribution would be for the top 20% to own 33% of the wealth. In fact, the top 20% owns about 82% of all the wealth in the US, and the bottom 60% own only 4% of the wealth (and the breakdown only gets more lopsided when we consider the top 5%, top 0.5%, and top 0.05%).

So, let us say that we democratically as a society decide that equality of opportunity should result in our fair wealth distribution as described above, and so we enact frictionless and fair policies, consistent with the Pareto principle, to move to the wealth distribution that Americans say would be fair now. How long would it take to get there? When would we arrive?

The answer is: never.

Under the Pareto principle, we cannot redistribute existing wealth, since doing so would make those from whom it is redistributed worse off.

We can try to get around this two ways: the first is, we only pass policies to ensure that future economic growth winds up being allocated, after taxes, in the distribution we have chosen as fair, or some facsimile thereof.

So we arrange our tax and other public policies to assure that not a cent of existing wealth is redistributed, but future growth winds up adding 33% of the total to the top 20%. Yes, I know we are talking unicorns and rainbows, but here's the point: even if we could do that, even if we did it for 10, or 20, or 50, or 100 years, or forever, we would never arrive at the wealth distribution we believe is fair. The top 20% would always have 33% of the wealth accumulated since now, and more than 33% of the pre-existing wealth. Thus, out into infinity, they would always have more than 33% of the total wealth. (Yes, I know what I've just written is a vast oversimplification blah blah blah. Note to economists: just consider it a "model," and then it's all good.)

The only way to get to 33% via future policies is to ensure that, for some period of time, the top 20% accumulate less than 33% of the new wealth, which we already have agreed is unfair, since we have agreed that they should have 33% of the wealth.

Needless to say, if our policies are far more incremental, which is of course far more likely, then we never even get close.

But wait, you say, people die. We simply change our estate tax laws to approximate what they were back in the 1930s, and prevent the transfer of $Billions to succeeding generations of heirs. There are several problems with this. The first is that, depending on how the tax laws are written, it will take decades to lifetimes to come to fruition. The second is the objection that existing plutocrats derive pleasure from the fact that they can dispose of their wealth, upon their death, as they see fit, and if that means ensuring that their heirs out unto the generations remain among the plutocrats, that is their right. If we interfere with that, we are making them very sad. The Pareto principle is violated.

The bottom line is, any choice by society to enact policies to move away from an existing distribution of wealth - even, let me emphasize, unearned, inherited wealth - violates the Pareto principle.

If Prof. Garcia's and DeLong's critique of inequality is correct, then surely it should not take a lifetime of resolute effort to approach a fairer result, and in fact the Pareto principle does not even permit that. The Pareto principle entrenches plutocracy.

So, I am sorry, Professors, but when it comes to entrenched inequality, there IS a problem

with the Pareto principle.

UPDATE; Just to be clear that this is not just about envying wealth, let's consider in our land of unicorns and rainbows that we have had a Rawlsian conference in which we have agreed to relentlessly enforce equality of opportunity. We then have a 10,000 year test run in which we reord the resulting distribution of wealth, which I'll call summation X.

We now go back into real history where we already have not had equality of opportunity, and we have any existing, different distribution of wealth. The Pareto priniple forbids us from ever arriving at summation X. A certain amount of wealth and assets can never be owned by those who should otherwise own them by dint of their efforts under conditions of equality of opporltunity. Why should we give our allegiance to such a principle?

======

P.S.: My primary solution to the above is to ignore the claimed utility as to heirs not yet in existence. I have no problem with Bill Gates or Henry Ford passing on their wealth, minus a reasonable tax rate, to their children or grandchildren. But by the time we get to great great grandchildren, inherited wealth should be taxed at confiscatory rates, e.g.,90%. I would only apply this to that portion of wealth that is inherited. If granddad leaves me $100 million, and by dint of acumen and industry I turn that into $1 Billion (after inflation) by the time of my death, only the inherited portion, i.e., the first $100 million, should be subject to the confiscatory rates.